| 1853 | 1869 |

|

|

[Editor's Note: The literature cited is identified in the 'Writings on Wallace' section at this site; the "S" numbers given refer to the item entry numbers in the 'Wallace Bibliography' section.]

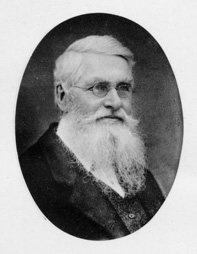

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913)

Página original: http://www.wku.edu/~smithch/index1.htm

| 1853 | 1869 |

|

|

[Editor's Note: The literature cited is identified in the 'Writings on Wallace' section at this site; the "S" numbers given refer to the item entry numbers in the 'Wallace Bibliography' section.]

1897

The Origins of an Evolutionist

(1823-1848)

The Origins of an Evolutionist

(1823-1848)

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), English naturalist, evolutionist, geographer, anthropologist, and social critic and theorist, was born 8 January 1823 at Usk, Gwent (formerly Monmouthshire). He was the third of four sons and eighth of nine children of Thomas Vere Wallace and Mary Anne Greenell, a middle-class English couple of modest means. The older Wallace was of Scottish descent (reputedly, of a line leading back to the famous William Wallace of medieval times); the Greenells were a relatively unremarkable but respectable English family that had lived in the area for generations. Thomas Wallace had trained for the law (and actually was sworn in as an attorney in 1792) but never practiced, income from inherited property securing him a life of leisure for the first fifteen years of his adulthood. With his marriage in 1807 things quickly changed, however, and he was forced into the first of what would turn out to be a long series of relatively unsuccessful ventures, including the publication of a literary magazine.

Young Alfred's childhood was a happy one, but at times difficult for lack of money. Four of his five older sisters did not live beyond the age of twenty-two, and Wallace himself was not always in the best of health. He found the grammar school he attended in Hertford rather tedious, but for a time was privy to plenty of good reading materials, his father being a town librarian for some years. About 1835 the elder Wallace was swindled out of his remaining property and the family fell on really hard times; young Wallace was forced to withdraw from school around Christmas 1836 and was sent to London to room with his older brother John. The ensuing several month experience was critical to his future intellectual development, as there he first came into contact with supporters of the utopian socialist Robert Owen. In his autobiography My Life (S729) he recollects that he even once heard Owen himself speak; from that point on he would describe himself in disciple terms.

By mid or late 1837 he had left London to join the eldest brother, William, in Bedfordshire. William owned a surveying business, and Wallace was to learn the trade. In 1839 he was temporarily apprenticed to a watchmaker, but by the end of the year he was again working with William, now based in Hereford. Over the next several years he picked up a number of trades-related skills and knowledge, particularly in drafting and map-making, geometry and trigonometry, building design and construction, mechanics, and agricultural chemistry. Moreover, he discovered that he really enjoyed the outdoor work involved in surveying. Soon he was starting to take an interest in the natural history of his surroundings, especially its botany, geology, and astronomy. While working in the area of the Hereford town of Kington in 1841 he became associated with the newly-formed Mechanic's Institution there; some months later, after moving over to the Welsh town of Neath, he began attending lectures given by the members of that area's various scientific societies. He also involved himself with the Neath Mechanics Institute, eventually giving his own lectures there on various technical and natural history subjects. The early 1840s also witnessed his first writing efforts: an essay (S1a) on the disposition of mechanics institutes written about 1841 found its way into a history of Kington published in 1845; two of his other essays from this early period (S1 and S623) are discussed in his 1905 autobiography My Life (S729).

In late 1843 a slow work period forced William Wallace to let his brother go. Alfred decided to apply for an open position at the Collegiate School in Leicester, where he was hired on as a master to teach drafting, surveying, English, and arithmetic. Now commenced another period central to his future path. Collegiate School had a good library, and there he was able to find and digest several important works on natural history and systematics; moreover, sometime during the year 1844 he made the acquaintance of another young amateur naturalist, Henry Walter Bates. Bates, though two years younger than Wallace, was already an accomplished entomologist, and his collections and collecting activities soon captured Wallace's interest. Around the same time Wallace saw his first demonstration of the practice of mesmerism, then dismissed by most as illusion or trickery. On investigating, however, he found he could personally reproduce many of the effects he had seen exhibited on stage, and learned his "first great lesson in the inquiry into these obscure fields of knowledge, never to accept the disbelief of great men, or their accusations of imposture or of imbecility, as of any weight when opposed to the repeated observation of facts by other men admittedly sane and honest" (S478).

In February of 1845 his brother William died unexpectedly and Wallace quit his teaching job at Leicester to return to surveying, now going through a boom period. But he soon found that running the business, even with the help of his brother John, involved responsibilities (such as fee collection) that he hated. He still had enough spare time, however, to continue with his natural history-related activities, and was even made a curator of the Neath Philosophical and Literary Institute's museum. He also kept up a correspondence with his friend Bates. A new book by William H. Edwards entitled A Voyage Up the River Amazon suggested a way out of his situation: he would turn professional and launch a self-sustaining natural history collecting expedition to South America. Bates was enlisted (undoubtedly with little effort), and the two young men (at the time Wallace was 25 and Bates 23) left for Pará (now called Belém), at the mouth of the Amazon, on 25 April 1848.

Travels in the Amazon and Malay Archipelago (1848-1862)

On 28 May 1848 Wallace and Bates disembarked at Pará and began to organize their operations. For nearly two years they worked as a team, but in March 1850 they split up (for reasons that have never been clarified). Wallace centered his activities in the middle Amazon and Rio Negro regions; Bates would remain in Amazonian South America eleven years, securing his permanent reputation as a leading naturalist and entomologist, and contributing significantly to the early development of the theory of natural selection through his elucidation of the concept of mimetic resemblance--"Batesian mimicry"--and various writings on biogeography. Wallace managed to ascend the Rio Negro system further than anyone else had to that point, and drafted a map of the Rio Negro region that proved accurate enough to become the standard for many years (see S11).

Apart from playing the role of collector and explorer, Wallace had an overriding reason for coming to the Amazon: to investigate the causes of organic evolution. His contacts with the Owenists had left him with an early interest in social/societal evolution, an interest that had extended itself in the direction of natural science with his mid-1840s readings of two crucial works: Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology, and Robert Chambers's Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Lyell's work had become the bible of uniformitarianism, and instilled in Wallace an appreciation of how long-term change could be effected through the operation of slow, ongoing processes. Vestiges was an early, popular, effort to examine the notion of biological evolution; it was a bit short on its appreciation of mechanism but argued pursuasively against both Creationism and Lamarckism. Wallace was apparently an instant convert to the feature arguments of each work, and very quickly recognized how he might go about demonstrating that evolution did in fact take place: by tracing out, over time and space, the geographical/geological records of individual phylogenies. He soon focused on two particular elements of this study: (1) the way geography limited or facilitated the extension of species range, and (2) how ecological station seemed to influence the shaping of adaptations more than did closeness of affinity with other forms. His investigation of these subjects included efforts to come to grips with the region's ornithology, entomology, primatology, ichthyology, botany, and physical geography, but in the end he was unable to come to any conclusion about the actual mechanism of evolutionary change. He also spent much time studying the ways of the native peoples he worked among, including collecting vocabularies of many of their languages (S714).

By early 1852 Wallace was in ill health and in no condition to proceed any further. He decided to quit South America, and began the long trip back down the Rio Negro and Amazon to Pará. When he finally reached the town that summer, he found that his younger brother Herbert, who had been working in the area since 1849 but had also decided to return to England, had caught yellow fever some months earlier and died. Moreover, and further to his dismay, most of the collections Wallace had been forwarding down the Amazon for the preceding two years had been delayed at the dock through a misunderstanding; he would therefore have to secure passage for these as well as himself. By early July he had been successful in so doing, and set out for England. Unfortunately, on August 6th the brig on which he was sailing caught fire and sank, taking almost all of his possessions along with it. For ten days Wallace and his comrades struggled to survive in a pair of badly leaking lifeboats, then were sighted and picked up by a passing cargo ship also making its way back to England. As luck would have it this vessel was also old and slow, and itself nearly foundered when hit by a series of storms. In all, Wallace's ocean crossing took eighty days.

When Wallace stepped back on English soil on 1 October 1852, he was faced with some decisions. His collections had been insured, but only to an extent buying him some time. He was now twenty-nine and reasonably well-known as a travelling naturalist, but he had not been able to come up with the key to the mystery of organic change. Further, he now had no collections he could study at his leisure that might help him do so. For eighteen months his activities were mixed: a vacation in Switzerland, attending professional meetings and delivering papers, and, finally, the production of two books: Palm Trees of the Amazon and Their Uses (S713) and A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro (S714). These made a slight but generally positive impression; the first was an ethnobotanical study based in part on drawings he had managed to save from the ship's fire; the second, a pleasant but not terribly profound account of his four years' work and travels.

With no other prospects immediately apparent, Wallace decided to carry on with his collecting activities. He chose the Indonesian Archipelago for his next base of operations, using his record of accomplishments to that point to secure a grant from the Royal Geographical Society covering his passage to what was referred to in those days as "the Malay Archipelago." He arrived in Singapore on 20 April 1854, to begin what would turn out to be the defining period of his life.

Wallace's name is now inextricably linked with his travels in the Indonesian region. He spent nearly eight full years there; during that period he undertook about seventy different expeditions resulting in a combined total of around 14,000 miles of travel. He visited every important island in the archipelago at least once, and several on multiple occasions. His collecting efforts produced the astonishing total of 125,660 specimens, including more than a thousand species new to science. The volume he later wrote describing his work and experiences there, The Malay Archipelago (S715), is the most celebrated of all writings on Indonesia, and ranks with a small handful of other works as one of the nineteenth century's best scientific travel books. Highlights of his adventures there include his study and capture of birds-of-paradise and orangutans, his many dealings with native peoples, and his residence on New Guinea (he was one of the very first Europeans to live there for any extended period).

Beyond his travel and collecting activities, Wallace's time in the Malay Archipelago was marked, of course, by the 1858 event that would assure his place in history. Three years earlier he had still been cogitating on the causes of organic evolution when an article by another naturalist prompted him to write and publish the essay 'On the Law Which Has Regulated the Introduction of New Species' (S20), a theoretical work that all but stated outright Wallace's belief in evolution. The paper was seen by Lyell, who thought highly of it and brought it to Darwin's attention. Darwin, however, took relatively little notice.

Now that he had a provisional model of the relation of biogeography to organic change, Wallace quickly applied the related concepts in two further studies, published in 1856 and 1857 (S26 & S38). In February of 1858, while suffering from an attack of malaria in the Moluccas (it is not fully certain which island he was actually on, though either Gilolo or Ternate seems the likely candidate), Wallace suddenly, and rather unexpectedly, connected the ideas of Thomas Malthus on the limits to population growth to a mechanism that might insure long-term organic change. This was the concept of the "survival of the fittest," in which those individual organisms that are best adapted to their local surroundings are seen to have a better chance of surviving, and thus of differentially passing along their traits to progeny. Excited over his discovery, Wallace penned an essay on the subject as soon as he was well enough to do so, and sent it off to Darwin. He had begun a correspondence with Darwin two years earlier and knew that he was generally interested in "the species question"; perhaps Darwin would be kind enough to bring the work, titled 'On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type,' (S43) to the attention of Lyell? Darwin was in fact willing to do so, but not for any reasons Wallace had anticipated. Darwin, as the now well-known story goes, had been entertaining very similar ideas for going on twenty years, and now a threat to his priority on the subject loomed. He contacted Lyell to plead for advice on how to meet what just about anyone would have to admit was a very awkward situation. Lyell and Joseph Hooker, a prominent botanist and another of Darwin's close friends, decided to present Wallace's essay, along with some unpublished fragments from Darwin's writings on the subject, to the next meeting of the Linnean Society. This took place on 1 July 1858, without obtaining Wallace's permission first (he was contacted only after the fact).

Whatever one thinks about Wallace's treatment in this matter, the events of summer 1858 did ensure that the world wouldn't have to wait any longer for its introduction to the concept of natural selection. Darwin had been working on a much larger tome on the subject that was still many years away from completion (and in fact never was completed); Wallace's bombshell had the immediate effect of forcing him to get together a more compact, readable, and, ultimately, probably more successful work. On the Origin of Species was published less than eighteen months later, in November of 1859. And, although Darwin would overshadow Wallace from that point on, Wallace's role in the affair was well enough known to insiders, at least, to ensure his future entry into the highest ranks of scientific dialogue. It should in all fairness to Darwin be noted that Wallace took full advantage of this opportunity, an opportunity he might not otherwise have received.

Wallace's discovery of natural selection occurred almost at the midpoint of his stay in the Malay Archipelago. He was to remain there four more years, continuing his agenda of systematically exploring and recording the circumstances of its faunas, floras, and peoples. By the end of his trip (and for the rest of his life) he was known as the greatest living authority on the region. He was especially known for his studies on its zoogeography, including his discovery and description of the faunal discontinuity that now bears his name. "Wallace's Line," extending between the islands of Bali and Lombok and Borneo and Sulawesi, marks the limits of eastern extent of many Asian animal forms and, conversely, the limits of western extent of many Australasian forms.

Wallace the Evolving Polymath (1862-1880)

Wallace left the Malay Archipelago in February of 1862 and returned to England on 1 April. His collecting activities had earned him a sizable nest egg with which he hoped he could retire to a quiet life as a country gentleman. First, however, there was the matter of coming to grips with the implications of his vast personal collection of specimens. For the next three years he immersed himself in them, producing a string of systematic revisions (mainly of birds and insects) and several interpretative works. Over that period (to the end of 1865) he presented at least sixteen papers at professional meetings, to the British Association, and Entomological, Zoological, Linnean, Anthropological and Geographical Societies. He soon met nearly every important English naturalist, and began to count many as friends.

In certain respects, the period 1862 through 1865 also represented a rather difficult time for Wallace. Eager to marry and settle down, he was rebuffed by one woman before wedding the eighteen year old daughter of a botanist friend in 1866. Although one of their three children would die only a few years later, their marriage was by all accounts a happy one: his wife Annie proved an excellent companion, and was well enough educated and sufficiently interested to help him from time to time with his work. Further, both Wallaces loved gardening, and spent many hours together pursuing this recreation. The real crisis for Wallace in the years after his return to England revolved, however, around his relation to the theory of natural selection. Although Wallace was known as a co-originator of the natural selection concept, the premature reading of the Ternate essay and Darwin's subsequent publication of On the Origin of Species led everyone to believe he was a full supporter of Darwinian doctrines. Subsequent events would prove he was not.

We unfortunately do not know whether Wallace felt at the time that his 1858 model of natural selection could be extended to explain the origin and/or development of humankind's higher mental and moral qualities. Surprisingly, he wrote not another word about natural selection (at least, in the sense of doing more than just mentioning it) until late 1863 (the classic analysis 'Remarks on the Rev. S. Haughton's Paper on the Bee's Cell, and on the Origin of Species,' S83). In 1864 he presented a milestone paper on the evolution of human races to the Anthropological Society: 'The Origin of Human Races and the Antiquity of Man Deduced From the Theory of "Natural Selection"' (S93). In this work Wallace sought to reconcile the positions of the monogenists and polygenists on human origins through an application of the general Darwinian model. But by 1865 at the latest (and possibly going back many years), he had been experiencing some doubt as to whether materialistic models, including Darwinism, could account for humankind's higher attributes. He began investigating the philosophy and manifestations of spiritualism, most likely (in my opinion) in an effort to complete what he had started in 1858. The result was a wholly new evolutionary synthesis, one in which a material process (natural selection) was understood to rule at the biological level, while a spiritual one (as described through spiritualism) operated at the level of consciousness. This overall approach was later taken up by the theosophists (Madame Blavatsky et al.), who based most of their more esoteric teachings (including, for example, theories of cyclic reincarnation) on ancient religious and literary texts, but who also acknowledged a role for natural selection in producing a Darwinian kind of material phylogenesis. (Wallace himself, however, would never take much interest in theosophy, considering it much too abstruse.)

Wallace's conversion to spiritualism in mid-1866 took many of his colleagues by surprise (Hooker would write in disbelief "that such a man should be a spiritualist is more wonderful than all the movements of all the planets"). Wallace spent a few years urging them to look into the matter in more detail, but few followed his lead. He would remain a spiritualist the rest of his days, never recounting his belief, and publishing some one hundred writings on the subject. It is in fact generally thought that Wallace's thinking regarding the application of Darwinian concepts to the development of humankind's higher attributes changed around 1865 in response to this apparent new influence in his life; I personally feel this is a mis-reading of the situation, and that the apparent "change" in his position simply represented a solidification of an already-existing, but not yet formally stated, evolutionary model.

Whatever one believes about the influences on Wallace's thoughts during this period, there can be no disagreement as to the sudden broadening of his attention that followed soon thereafter. In 1865 he produced his first published writing on politics (S110); in 1866 writings on geodesy (S115 & S116); in 1867 his first of many treatments of glacial features (S124); and in 1869 the first of several essays on museum organization (S143). Primarily, however, he was gaining recognition as one of Darwin's two main (the other being Thomas Huxley) "right-hand men." His most important 1860s works in that direction include S83, S93, S96, S121, S134, S136, S139, S140, S146, and S155. His reputation as a naturalist soon extended itself to the popular arena with the publication of his hugely successful The Malay Archipelago (S715) in early 1869, and the essay collection Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection (S716) a year later.

In the decade that followed, Wallace published over 150 works, including essays, letters, reviews, book notices, and monographs. His scientific writings would focus on natural selection, geographical distribution, and glaciology, and include three classic books: The Geographical Distribution of Animals (S718) in 1876, Tropical Nature, and Other Essays (S719) in 1878, and Island Life (S721) in 1880. Each work is still frequently referred to today: S718, for its formalization of the faunal region concept and treatment of zoogeographical methodology; S719, for its attention to the causes and characteristics of tropical floras and faunas (including its discussion of the concept of latitudinal diversity gradients); and S721, for its systemization of island types and biotas, and relation of glaciation processes to the known characteristics of geographical distribution of plants and animals. In Wallace's work in biology and anthropology, further departures from Darwinian thinking were evident. He continued to argue against some of Darwin's positions on human evolution, and in addition the latter's approach to sexual selection and several biogeographic matters. His 1870s writings were also characterized by an increased attention to social issues. In 1870 he spoke out against government aid to science (S157 & S158); in 1873 he produced essays on the Church of England (S225), free trade principles (S231), and the abolishment of trusts (S236); in 1878 he wrote on a suburban forest management issue (S292); and in 1879, again on free trade (S306, S310 & S312).

Meanwhile, personal problems were creating a considerable distraction. Most of the profits accrued from his Malay collections were badly invested, and lost. He was not well suited for most kinds of permanent positions, and despite applying for a number of them never succeeded in landing one. He took on odd jobs (editing other naturalists' manuscripts, correcting state-administered examinations, giving lectures, etc.) to help make ends meet, and moved progressively further and further from London to minimize costs and find more suitable living quarters. In 1870 Wallace took up a 500.-pound challenge from a flat-earther to produce a proof that the earth was not flat; he won the challenge with a neatly conceived demonstration but, on a technicality, not a penny of the wager, and was seriously harassed by the loser for over ten years. Eventually his financial situation degenerated far enough to cause a friend to intervene; in 1881, with help from Darwin (see Colp 1992), the government was convinced to grant him an annual civil list pension of 200. pounds for his services to science. It was not enough to live on, but it helped.

Wallace the Soproblems associated with land tenure, and in 1870, at the special invitation of John Stuart Mill, had even become peripherally involved with the latter's Land Tenure Reform Association. But in early 1881, following the publication of his 'How to Nationalize the Land' (S329), he fully committed himself to the debate by helping start the Land Nationalisation Society. He also became its first President, holding that position until his death, over thirty years later (though after 1895 his participation in the organization's work was more inspirational than actual). Wallace's two most important writings on land were his Land Nationalisation (S722), published in 1882, and 1883's 'The "Why" and the "How" of Land Nationalisation' (S365). In these he argued that the State should, over the long-term, buy out large land holdings and then institute an elaborate rent system based on a combination of location-specific and value-added-by-renter considerations. Wallace's writings on land nationalization include many ideas in advance of their time, including suggestions for the legislated protection of rural lands and historical monuments, the construction of greenbelts and parks, and arguments for suburban and rural re-population and organization. In the early 1880s he also became interested in the anti-vaccination movement. As one of its most powerful spokespersons he would produce a series of impassioned writings (S374, S420, S536 & S616) that featured statistical epidemiological arguments, a great novelty for its time.

Wallace also took up the causes of the labor movement. He was an early proponent of overtime pay rates, but was against strikes: instead, he argued, employees should donate a portion of their pay to funds that could later be used to effect company buy-outs. Eventually he came around to endorsing socialism, but only as late as 1890, on his reading of the American Edward Bellamy's best-selling utopian novel Looking Backward. As mentioned earlier, Wallace had since his early teen years had a genuine love for the work of Robert Owen, but had never quite believed in the large-scale practicality of Owen's approach. Neither had he been quite sure about its possible incursion on individual rights and freedoms. Looking Backward changed his mind on both issues. From 1890 on, Wallace would view socialism as a means whereby the average person might obtain a certain basic and acceptable standard of living; freedom from worrying over basics would then (in theory) allow a re-directioning of attention toward various means of moral/ethical self-improvement (including spiritualism). His motto (borrowed from the English sociologist and writer Benjamin Kidd) would become "Equality of opportunity!", a plea for social justice.

The preceding list by no means exhausts the range of non-natural science-related subjects that Wallace at one time or another addressed. For example, he was an early supporter of women's suffrage, and was much admired by the members of the women's movement for his unqualified stand on the matter. He also came down heavily on many occasions on societal and governmental responses to eugenics, poverty, militarism, imperialism, and institutional punishment. On several occasions (S552, S553, S556 & S557) he wrote on the advantages of implementing a paper money standard; his efforts were later recognized by twentieth century economists interested in currency stabilization theory (the renowned American economist Irving Fisher even dedicated a book to him!). He sparred with the legal system at times, suggesting changes in the means of dealing with inherited wealth and trusts. He wrote two essays (S491 & S635) on how to re-establish confidence in the House of Lords, and one on how to revitalize the Church of England (S225). Many of the more conservative of the social and institutional elite came to wince at the mere mention of his name.

Although Wallace's travels as a self-supporting naturalist/explorer had ended with his return to England in 1862, he did not lead an entirely sedentary life his remaining years. As already mentioned, he began to move away from London as early as the 1860s; by 1881 he was in Godalming, in 1889, Parkstone, and then, finally, Broadstone (near Wimborne, Dorset, and the English Channel) in 1902. For many years (until 1890) he travelled around the better part of England giving lectures and attending meetings, and even to Scotland and Ireland. He and his wife also spent several vacations and "botanizing excursions" in locations ranging from Wales and the Lake Country to Switzerland. In 1896 he gave an invited lecture on progress in the nineteenth century in the town of Davos in the latter country. But the main adventure of his post-Malay Archipelago life was a ten-month lecture tour to the United States and Canada in 1886 and 1887.

In late 1885 Wallace was invited to give a series of lectures on Darwinism at the Lowell Institute in Massachusetts. Once this obligation was met he would be free to arrange such other lectures as he might wish. For six months in late 1886 and early 1887 he stayed mainly in the vicinities of Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C., where he met countless individuals of note, up to and including President Cleveland. In early April of 1887 he set out across the country, reaching California in late May of that year. There he was reunited with his older brother John, who he hadn't seen for nearly forty years. For several weeks he vacationed and lectured; one of his presentations was a talk on spiritualism entitled 'If a Man Die, Shall He Live Again?' (S398)--probably the single most successful lecture he ever gave. Significant events from his stay in the San Francisco area included tours of nearby redwood groves (in the company of the eminent naturalist John Muir), Yosemite Valley, and the future site of Stanford University (with Leland Stanford himself, with whom he had become intimate some months earlier in Washington, D.C.). In early July he left California to return eastward, ultimately back to England.

The American tour became the inspiration for Wallace's next major book, in 1889. Titled Darwinism (S724), it consisted largely of the topics he had lectured on, presented one chapter at a time. It did very well, and remains one of his most frequently cited works. Darwinism, while perhaps the highpoint of his later scientific work, was nevertheless only a very small part of it. Although social studies were absorbing more and more of his attention throughout the 1880s and 1890s, he was still left with plenty of time to crank out a steady stream of writings on more scientific subjects. During the 1890s alone he again published a total of over 150 works, dozens of these dealing with evolutionary, biogeographic, and physical geography subjects.

By the turn of the century, Wallace was very probably Britain's best known naturalist. By the end of his life, moreover, he may well have owned (based on evidence gleaned from contemporary sources) one of the world's most recognized names. While simultaneously continuing to publish scores of short works, between the years 1898 and 1910--mostly during his ninth decade--he managed to turn out (i.e., as author and/or editor) well over four thousand pages of monographic writings! His final two books were published in the year of his death, 1913. He remained active into his ninety-first year but slowly weakened in his final months. He died in his sleep at Broadstone on 7 November 1913; three days later his remains were buried nearby. On 1 November 1915 a medallion bearing his name was placed in Westminster Abbey.

Despite Wallace's radical associations and links with spiritualism, he was well honored during his lifetime (and he most likely would have been even more so had he not made it clear early on that he was not particularly interested in receiving honoraria). He was awarded honorary doctorates from the University of Dublin in 1882 and Oxford University in 1889, and important medals from the Royal Society in 1868, 1890 and 1908, the Société de Geographie in 1870, and the Linnean Society in 1892 and 1908. He even received the Order of Merit from the Crown in 1908--quite an honor for such an anti-establishment radical. He became a (reluctant) member of the Royal Society in 1893, and at one time or another had professional affiliations with the Royal Geographical Society, Linnean Society, Zoological Society, Royal Entomological Society, Ethnological Society (though apparently not as a member), British Association for the Advancement of Science, Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences, British National Association of Spiritualists, Land Nationalisation Society, Anti-Vaccination League, and several lesser organizations.

Physical descriptions of Wallace dwell on his height (as a young man he was six feet one inch tall), long beard (maintained from his days in the Malay Archipelago on), and snow-white hair (starting in his fifties). He had a fundamentally lean build, and as the years passed came to walk with a bit of a stoop. His eyesight was not strong, with the result that his sparkling blue eyes were framed by spectacles for most of his life. He experienced various illnesses and ailments throughout his life, none of which individually seems to have had any great negative effect on his productivity.

As a person Wallace was decent to a fault; he possessed an apparently infinite tolerance for the weaknesses of others (and was surely victimized on a number of occasions as a result), but he was also known for not suffering fools gladly. He thrived on public debate, but was personally modest, shy, and self-effacing. Still, by all accounts he was good company when at ease, and was much in demand as a public speaker. He also had a solid reputation as a writer and reviewer, and for all his "isms" was generally regarded by his peers as one of the period's greatest scientific reasoners.

Wallace's Accomplishments: A Summary List

The assessment of Wallace's contribution remains a work in progress. In what follows I briefly outline what various sources have pointed to as his noteworthy achievements. The entries are arranged chronologically as possible; most include one or more referrals to related (his own, and secondary source) writings identified in the 'Wallace Bibliography' and 'Writings on Wallace' sections.

Biographical Sources

- in 1851 ascends the Rio Negro/Uaupés River in South America further than any previous European; constructs a dependable map of the course of the river (S11, S714)

- in 1852 advances the riverine barrier hypothesis of species distribution patterns in Amazonia (S8)

- through his four-year collecting expedition to Amazonia (1848-1852) becomes recognized as an expert on the region's natural history (S3-S13, S713, S714; Beddall 1969, Maslow 1996, Raby 1997, Knapp 1999)

- adopts the position, unusual for nineteenth-century workers, that uncivilized peoples are on the whole neither morally nor intellectually inferior to civilized peoples

- in 1855 writes and publishes essay connecting the facts of geographical and geological distribution to evolution (S20; George 1964, McKinney 1966 & 1972, Brooks 1984)

- in 1855 engages in the first extensive collecting efforts and field studies on the orangutan (S23, S24, S26, S30, S715; Harrisson 1960, Raby 1997)

- investigates and describes the faunal discontinuity now known as "Wallace's Line," c1856-1862 (S53, S78, S715; Mayr 1944, George 1981, Whitmore 1981, Camerini 1993, Diamond 1997, Van Oosterzee 1997)

- engages in extensive collecting efforts and field studies on birds of paradise, c1857-1860 (S37, S48, S55, S67, S715; Camerini 1996, Raby 1997)

- in 1858 writes and publishes essay introducing the concept of natural selection (S43; McKinney 1966 & 1972, Beddall 1968 & 1988, Moody 1971, Bowler 1976, Brackman 1980, Brooks 1984, Gardiner 1995, Stevens 1995, England 1997, Moore 1997)

- in 1858 becomes one of the first Europeans to set up a residence in New Guinea (S51, S65, S715)

- opines that Papuans are not Malays (S51, S301, S715)

- defends and eventually institutionalizes the faunal realms classification scheme of Philip L. Sclater (S52, S360, S494, S500, S718; George 1964, Nelson 1978, Smith 1983 & 1989)

- in 1860 suggests that an international review board be established to settle questions regarding competing claims of priority in zoological nomenclature (S63)

- collects 125,660 specimens (mostly birds and insects) during the eight-year (1854-1862) expedition to the Malay Archipelago (S715; George 1979, Baker 1996, Camerini 1996 & 1997, Raby 1997, Daws & Fujita 1999)

- in 1863 proposes a Darwinian explanation for the hexagonal construction of bees' cells (S83)

- in 1864 introduces a model of human racial differentiation based on the theory of natural selection (S93; Kottler 1974, Koch-Weser 1977, Schwartz 1984, Shermer 1991)

- in 1864 introduces the concept of polymorphism (S96, S98; George 1964, Blaisdell 1992)

- in 1864 suggests that female butterflies may be more variable than males (S96)

- makes fundamental early contributions to the theory of mimicry (S72, S96, S98, S121, S123, S134, S176, S272; Remington 1963, George 1964, Kimler 1983, Blaisdell 1992)

- constructs an evolutionarily-consistent theory of the necessity of aging and death (S419)

- initiates the study of protective coloration in plants and animals, including inventing the concepts of "alluring colors," "deflexion colors," "warning colors," and "disruptive colors" (S129, S134, S138, S257, S272, S304, S318, S724; George 1964, Cronin 1991, Blaisdell 1992)

- in 1867 opines that Polynesian peoples are not of Malayan origin (S131; George 1964)

- in several essays contributes suggestions for the design of museums (S143, S170, S401, S402, S404, S405)

- in The Malay Archipelago (1869) produces a study that becomes the most famous work ever written on its subject, and one of the greatest nineteenth century scientific travel books (S715; Bastin 1986)

- in 1869 is one of the first to describe surface manifestations of internal soliton waves (S715)

- becomes known as the greatest living authority on the Indonesian region

- in 1870 advances an estimate of the age of the earth based in part on inferences drawn from land surface erosion rates (S146, S159, S367, S721; Marchant 1916, George 1964)

- becomes known as one of Darwin's most persistent and successful defenders (S83, S107, S108, S140, S155, S175, S198, S210, S724)

- in 1874 is the first to link bird migration to natural selection (S244)

- presents a range of evidence defending the permanence of the continental masses and oceanic basins (S269, S453, S718, S721; Fichman 1977, Michaux 1991)

- promotes the use of ecogeographically-arranged displays of animal and plant forms in book figures and museum displays, leading to the development of the "faunal diorama" (S401, S718)

- in 1877 is one of the first to ask why color vision has evolved, and to suggest a possible answer (S272)

- in 1877 introduces the concept of recognition marks (S272, S389, S395, S485, S724; George 1964, Cronin 1991)

- in 1878 is one of the first to consider the causes of latitudinal diversity gradients and related aspects of (what are now known as) r- and K-selection (S289, S290)

- in 1879 describes the causes of disjunct distribution patterns (S302; George 1964)

- develops the first theory of the causes of continental glaciation combining geographical and astronomical factors (S313, S520, S521, S721; Marchant 1916, George 1964)

- makes early contributions to the systematic classification of island types (S316, S393, S465, S721)

- in 1880 presents the theory of alpine corridor dispersal to explain the existence of temperate and arctic plants in lower latitude locations (S721, S724)

- in 1880 becomes a vocal supporter of the ideas of American economist Henry George, helping him gain prominence (S369, S722; Silagi 1989, Andelson 1993, Jones 1994, Gaffney 1997)

- develops a model of rent assessment based on (1) the location of a parcel of land relative to other services, plus (2) value added to the parcel by the renter (S329, S365, S466, S471)

- is one of the first to draw attention to and provide evidence for the mouth-gesture theory of the origin of language (S169, S337, S518; George 1964)

- in 1882 proposes that greenbelts be established near urban areas (S722; George 1964)

- in 1882 proposes that rural areas and historic monuments receive legislated protection (S722; George 1964)

- in 1882 makes the suggestion that explosives be stored underwater (S562a, S729)

- in 1882 draws attention to, and extends, Müller's work on mimicry (S353, S359; Remington 1963, George 1964, Kimler 1983)

- in his analyses of small-pox incidence becomes one of the first to use statistical arguments in an attempt to resolve an epidemiological question (S374, S420, S536, S616; Clements 1983, Scarpelli 1985 & 1992)

- in 1885 suggests it become law that all manufactured goods carry labels specifying their component materials, and that standards for those materials be set and administered by institutions representing each class of manufactures (S723)

- through the book The Malay Archipelago becomes one of the most important influences on the writings of novelist Joseph Conrad (Clemens 1939, Sherry 1966, Hunter 1983, Houston 1997)

- in 1889 describes what is now known as the "Wallace effect," the process of selection for reproductive isolation (S724; Marchant 1916, Mayr 1959, Grant 1966, Sawyer & Hartl 1981)

- in 1889 discusses the significance of symmetrical color patterns in animals (S724)

- criticizes eugenics and develops a model of "human selection" based on elevating the economic status of women (S427, S445, S649, S733; Clements 1983)

- draws attention to work being done to investigate Southern Hemisphere glaciation episodes (S172, S456, S472, S480, S482)

- in 1893 advances the opinion that the Australian aborigines are a Caucasian people (S583, S720)

- makes contributions to the theory of ice movement in glaciers (S124, S184, S233, S462, S481, S484)

- in 1893 all but proves Sir Andrew Ramsay's glacial origin theory of alpine lake basins (S462, S481, S484, S489)

- in 1898 becomes an early proponent of using paper money as the standard of value (S552, S553, S556, S557; Fisher 1920, Patinkin 1993)

- points to deserts and volcanoes as representing important sources of material for condensation nuclei, with special emphasis on the role of dust (S547, S728)

- in 1899 suggests that employees collectively put aside pay otherwise lost to strikes for the longer-term purpose of company buy-outs (S560)

- in 1899 suggests using fire hoses as a means of riot control (S567)

- in 1903 becomes one of the first to identify the range of concepts inherent in what is now known as the "anthropic principle" (S728; Kazyutinsky & Balashov 1989, Balashov 1991)

- in the early 1900s pioneers the field of exobiology with studies on the likelihood of life-sponsoring conditions in other parts of the universe (S602, S728, S730; Tipler 1981, Kevin 1985)

- in 1907 debunks Perceval Lowell's idea that Mars is inhabited (S730; Hoyt 1976, Heffernan 1981, Hetherington 1981, Gould 1996-1997)

- in 1910 is one of the first to suggest that the animal extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene might have been due to over-hunting by prehistoric humans (S732)

- in 1913 expresses support for creating a minimum wage standard (S734)

- in 1913 expresses support for paying double-time rates for overtime work (S734; Marchant 1916 (1891 letter from ARW to his daughter))

- eventually attains status as history's pre-eminent tropical naturalist (S713, S714, S715, S719, S720; Beddall 1969, Quammen 1996, Raby 1997)

- eventually becomes known as the "father of zoogeography" for his many contributions to this field (S20, S53, S78, S715, S718, S719, S721; George 1964, Browne 1983, Quammen 1996)

The best overall source of information on Wallace's life is

still by far his own My Life (S729), published in two volumes in 1905.

Marchant (1916) provides an early biographical review which includes many of

Wallace's personal letters. Other general biographies include Marchant (1913),

Hogben (1918), George (1964), Williams-Ellis (1966), Fichman (1981), Clements

(1983), and Hughes (1997). Much information of a biographical nature is included

in Poulton (1923-1924), Huxley (1927), Beddall (1969), McKinney (1972 &

1976), Brackman (1980), Brooks (1984), Hughes (1989), Quammen (1996), Raby

(1997), Severin (1998), Knapp (1999), Rice (1999), and Wilson (2000). McKinney

(1972) lists the locations of many of the personal letters known to exist as of

the date of that publication, but additional ones continue to surface; Shermer

(1991) gives additional information on primary sources.

Trabalho Original

On the Tendency of Varieties to

Depart Indefinitely From the

Original Type (S43: 1858)

[Editor's Note: This is the famous "Ternate essay" introducing

natural selection that Wallace sent to Charles Darwin in February of 1858. This

paper, along with excerpts from two unpublished writings by Darwin, was read

before a special meeting of the Linnean Society of London on 1 July 1858, and

published on pages 53-62 of Volume 3 of that Society's Proceedings

series. It should thus be noted that, frequently seen comments to the contrary

notwithstanding, Wallace did not "publish a paper describing natural

selection before Darwin did"--in fact, there is conclusive historical

evidence1 that even Wallace's own paper had not been intended for

publication in the form in which it was sent to Darwin.]

One of the strongest arguments which have been adduced to prove the original and permanent distinctness of species is, that varieties produced in a state of domesticity are more or less unstable, and often have a tendency, if left to themselves, to return to the normal form of the parent species; and this instability is considered to be a distinctive peculiarity of all varieties, even of those occurring among wild animals in a state of nature, and to constitute a provision for preserving unchanged the originally created distinct species.

In the absence or scarcity of facts and observations as to varieties occurring among wild animals, this argument has had great weight with naturalists, and has led to a very general and somewhat prejudiced belief in the stability of species. Equally general, however, is the belief in what are called "permanent or true varieties,"--races of animals which continually propagate their like, but which differ so slightly (although constantly) from some other race, that the one is considered to be a variety of the other. Which is the variety and which the original species, there is generally no means of determining, except in those rare cases in which the one race has been known to produce an offspring unlike itself and resembling the other. This, however, would seem quite incompatible with the "permanent invariability of species," but the difficulty is overcome by assuming that such varieties have strict limits, and can never again vary further from the original type, although they may return to it, which, from the analogy of the domesticated animals, is considered to be highly probable, if not certainly proved.

It will be observed that this argument rests entirely on the assumption, that varieties occurring in a state of nature are in all respects analogous to or even identical with those of domestic animals, and are governed by the same laws as regards their permanence or further variation. But it is the object of the present paper to show that this assumption is altogether false, that there is a general principle in nature which will cause many varieties to survive the parent species, and to give rise to successive variations departing further and further from the original type, and which also produces, in domesticated animals, the tendency of varieties to return to the parent form.

The life of wild animals is a struggle for existence. The full exertion of all their faculties and all their energies is required to preserve their own existence and provide for that of their infant offspring. The possibility of procuring food during the least favourable seasons, and of escaping the attacks of their most dangerous enemies, are the primary conditions which determine the existence both of individuals and of entire species. These conditions will also determine the population of a species; and by a careful consideration of all the circumstances we may be enabled to comprehend, and in some degree to explain, what at first sight appears so inexplicable--the excessive abundance of some species, while others closely allied to them are very rare.

The general proportion that must obtain between certain groups of animals is readily seen. Large animals cannot be so abundant as small ones; the carnivora must be less numerous than the herbivora; eagles and lions can never be so plentiful as pigeons and antelopes; the wild asses of the Tartarian deserts cannot equal in numbers the horses of the more luxuriant prairies and pampas of America. The greater or less fecundity of an animal is often considered to be one of the chief causes of its abundance or scarcity; but a consideration of the facts will show us that it really has little or nothing to do with the matter. Even the least prolific of animals would increase rapidly if unchecked, whereas it is evident that the animal population of the globe must be stationary, or perhaps, through the influence of man, decreasing. Fluctuations there may be; but permanent increase, except in restricted localities, is almost impossible. For example, our own observation must convince us that birds do not go on increasing every year in a geometrical ratio, as they would do, were there not some powerful check to their natural increase. Very few birds produce less than two young ones each year, while many have six, eight, or ten; four will certainly be below the average; and if we suppose that each pair produce young only four times in their life, that will also be below the average, supposing them not to die either by violence or want of food. Yet at this rate how tremendous would be the increase in a few years from a single pair! A simple calculation will show that in fifteen years each pair of birds would have increased to nearly ten millions!2 whereas we have no reason to believe that the number of the birds of any country increases at all in fifteen or in one hundred and fifty years. With such powers of increase the population must have reached its limits, and have become stationary, in a very few years after the origin of each species. It is evident, therefore, that each year an immense number of birds must perish--as many in fact as are born; and as on the lowest calculation the progeny are each year twice as numerous as their parents, it follows that, whatever be the average number of individuals existing in any given country, twice that number must perish annually,--a striking result, but one which seems at least highly probable, and is perhaps under rather than over the truth. It would therefore appear that, as far as the continuance of the species and the keeping up the average number of individuals are concerned, large broods are superfluous. On the average all above one become food for hawks and kites, wild cats and weasels, or perish of cold and hunger as winter comes on. This is strikingly proved by the case of particular species; for we find that their abundance in individuals bears no relation whatever to their fertility in producing offspring. Perhaps the most remarkable instance of an immense bird population is that of the passenger pigeon of the United States, which lays only one, or at most two eggs, and is said to rear generally but one young one. Why is this bird so extraordinarily abundant, while others producing two or three times as many young are much less plentiful? The explanation is not difficult. The food most congenial to this species, and on which it thrives best, is abundantly distributed over a very extensive region, offering such differences of soil and climate, that in one part or another of the area the supply never fails. The bird is capable of a very rapid and long-continued flight, so that it can pass without fatigue over the whole of the district it inhabits, and as soon as the supply of food begins to fail in one place is able to discover a fresh feeding-ground. This example strikingly shows us that the procuring a constant supply of wholesome food is almost the sole condition requisite for ensuring the rapid increase of a given species, since neither the limited fecundity, nor the unrestrained attacks of birds of prey and of man are here sufficient to check it. In no other birds are these peculiar circumstances so strikingly combined. Either their food is more liable to failure, or they have not sufficient power of wing to search for it over an extensive area, or during some season of the year it becomes very scarce, and less wholesome substitutes have to be found; and thus, though more fertile in offspring, they can never increase beyond the supply of food in the least favourable seasons. Many birds can only exist by migrating, when their food becomes scarce, to regions possessing a milder, or at least a different climate, though, as these migrating birds are seldom excessively abundant, it is evident that the countries they visit are still deficient in a constant and abundant supply of wholesome food. Those whose organization does not permit them to migrate when their food becomes periodically scarce, can never attain a large population. This is probably the reason why woodpeckers are scarce with us, while in the tropics they are among the most abundant of solitary birds. Thus the house sparrow is more abundant than the redbreast, because its food is more constant and plentiful,--seeds of grasses being preserved during the winter, and our farm-yards and stubble-fields furnishing an almost inexhaustible supply. Why, as a general rule, are aquatic, and especially sea birds, very numerous in individuals? Not because they are more prolific than others, generally the contrary; but because their food never fails, the sea-shores and river-banks daily swarming with a fresh supply of small mollusca and crustacea. Exactly the same laws will apply to mammals. Wild cats are prolific and have few enemies; why then are they never as abundant as rabbits? The only intelligible answer is, that their supply of food is more precarious. It appears evident, therefore, that so long as a country remains physically unchanged, the numbers of its animal population cannot materially increase. If one species does so, some others requiring the same kind of food must diminish in proportion. The numbers that die annually must be immense; and as the individual existence of each animal depends upon itself, those that die must be the weakest--the very young, the aged, and the diseased,--while those that prolong their existence can only be the most perfect in health and vigour--those who are best able to obtain food regularly, and avoid their numerous enemies. It is, as we commenced by remarking, "a struggle for existence," in which the weakest and least perfectly organized must always succumb.

Now it is clear that what takes place among the individuals of a species must also occur among the several allied species of a group,--viz. that those which are best adapted to obtain a regular supply of food, and to defend themselves against the attacks of their enemies and the vicissitudes of the seasons, must necessarily obtain and preserve a superiority in population; while those species which from some defect of power or organization are the least capable of counteracting the vicissitudes of food, supply, &c., must diminish in numbers, and, in extreme cases, become altogether extinct. Between these extremes the species will present various degrees of capacity for ensuring the means of preserving life; and it is thus we account for the abundance or rarity of species. Our ignorance will generally prevent us from accurately tracing the effects to their causes; but could we become perfectly acquainted with the organization and habits of the various species of animals, and could we measure the capacity of each for performing the different acts necessary to its safety and existence under all the varying circumstances by which it is surrounded, we might be able even to calculate the proportionate abundance of individuals which is the necessary result.

If now we have succeeded in establishing these two points--1st, that the animal population of a country is generally stationary, being kept down by a periodical deficiency of food, and other checks; and, 2nd, that the comparative abundance or scarcity of the individuals of the several species is entirely due to their organization and resulting habits, which, rendering it more difficult to procure a regular supply of food and to provide for their personal safety in some cases than in others, can only be balanced by a difference in the population[s] which have to exist in a given area--we shall be in a condition to proceed to the consideration of varieties, to which the preceding remarks have a direct and very important application.

Most or perhaps all the variations from the typical form of a species must have some definite effect, however slight, on the habits or capacities of the individuals. Even a change of colour might, by rendering them more or less distinguishable, affect their safety; a greater or less development of hair might modify their habits. More important changes, such as an increase in the power or dimensions of the limbs or any of the external organs, would more or less affect their mode of procuring food or the range of country which they inhabit. It is also evident that most changes would affect, either favourably or adversely, the powers of prolonging existence. An antelope with shorter or weaker legs must necessarily suffer more from the attacks of the feline carnivora; the passenger pigeon with less powerful wings would sooner or later be affected in its powers of procuring a regular supply of food; and in both cases the result must necessarily be a diminution of the population of the modified species. If, on the other hand, any species should produce a variety having slightly increased powers of preserving existence, that variety must inevitably in time acquire a superiority in numbers. These results must follow as surely as old age, intemperance, or scarcity of food produce an increased mortality. In both cases there may be many individual exceptions; but on the average the rule will invariably be found to hold good. All varieties will therefore fall into two classes--those which under the same conditions would never reach the population of the parent species, and those which would in time obtain and keep a numerical superiority. Now, let some alteration of physical conditions occur in the district--a long period of drought, a destruction of vegetation by locusts, the irruption of some new carnivorous animal seeking "pastures new"--any change in fact tending to render existence more difficult to the species in question, and tasking its utmost powers to avoid complete extermination; it is evident that, of all the individuals composing the species, those forming the least numerous and most feebly organized variety would suffer first, and, were the pressure severe, must soon become extinct. The same causes continuing in action, the parent species would next suffer, would gradually diminish in numbers, and with a recurrence of similar unfavourable conditions might also become extinct. The superior variety would then alone remain, and on a return to favourable circumstances would rapidly increase in numbers and occupy the place of the extinct species and variety.

The variety would now have replaced the species, of which it would be a more perfectly developed and more highly organized form. It would be in all respects better adapted to secure its safety, and to prolong its individual existence and that of the race. Such a variety could not return to the original form; for that form is an inferior one, and could never compete with it for existence. Granted, therefore, a "tendency" to reproduce the original type of the species, still the variety must ever remain preponderant in numbers, and under adverse physical conditions again alone survive. But this new, improved, and populous race might itself, in course of time, give rise to new varieties, exhibiting several diverging modifications of form, any of which, tending to increase the facilities for preserving existence, must, by the same general law, in their turn become predominant. Here, then, we have progression and continued divergence deduced from the general laws which regulate the existence of animals in a state of nature, and from the undisputed fact that varieties do frequently occur. It is not, however, contended that this result would be invariable; a change of physical conditions in the district might at times materially modify it, rendering the race which had been the most capable of supporting existence under the former conditions now the least so, and even causing the extinction of the newer and, for a time, superior race, while the old or parent species and its first inferior varieties continued to flourish. Variations in unimportant parts might also occur, having no perceptible effect on the life-preserving powers; and the varieties so furnished might run a course parallel with the parent species, either giving rise to further variations or returning to the former type. All we argue for is, that certain varieties have a tendency to maintain their existence longer than the original species, and this tendency must make itself felt; for though the doctrine of chances or averages can never be trusted to on a limited scale, yet, if applied to high numbers, the results come nearer to what theory demands, and, as we approach to an infinity of examples, become strictly accurate. Now the scale on which nature works is so vast--the numbers of individuals and periods of time with which she deals approach so near to infinity, that any cause, however slight, and however liable to be veiled and counteracted by accidental circumstances, must in the end produce its full legitimate results.

Let us now turn to domesticated animals, and inquire how varieties produced among them are affected by the principles here enunciated. The essential difference in the condition of wild and domestic animals is this,--that among the former, their well-being and very existence depend upon the full exercise and healthy condition of all their senses and physical powers, whereas, among the latter, these are only partially exercised, and in some cases are absolutely unused. A wild animal has to search, and often to labour, for every mouthful of food--to exercise sight, hearing, and smell in seeking it, and in avoiding dangers, in procuring shelter from the inclemency of the seasons, and in providing for the subsistence and safety of its offspring. There is no muscle of its body that is not called into daily and hourly activity; there is no sense or faculty that is not strengthened by continual exercise. The domestic animal, on the other hand, has food provided for it, is sheltered, and often confined, to guard it against the vicissitudes of the seasons, is carefully secured from the attacks of its natural enemies, and seldom even rears its young without human assistance. Half of its senses and faculties are quite useless; and the other half are but occasionally called into feeble exercise, while even its muscular system is only irregularly called into action.

Now when a variety of such an animal occurs, having increased power or capacity in any organ or sense, such increase is totally useless, is never called into action, and may even exist without the animal ever becoming aware of it. In the wild animal, on the contrary, all its faculties and powers being brought into full action for the necessities of existence, any increase becomes immediately available, is strengthened by exercise, and must even slightly modify the food, the habits, and the whole economy of the race. It creates as it were a new animal, one of superior powers, and which will necessarily increase in numbers and outlive those inferior to it.

Again, in the domesticated animal all variations have an equal chance of continuance; and those which would decidedly render a wild animal unable to compete with its fellows and continue its existence are no disadvantage whatever in a state of domesticity. Our quickly fattening pigs, short-legged sheep, pouter pigeons, and poodle dogs could never have come into existence in a state of nature, because the very first step towards such inferior forms would have led to the rapid extinction of the race; still less could they now exist in competition with their wild allies. The great speed but slight endurance of the race horse, the unwieldy strength of the ploughman's team, would both be useless in a state of nature. If turned wild on the pampas, such animals would probably soon become extinct, or under favourable circumstances might each lose those extreme qualities which would never be called into action, and in a few generations would revert to a common type, which must be that in which the various powers and faculties are so proportioned to each other as to be best adapted to procure food and secure safety,--that in which by the full exercise of every part of his organization the animal can alone continue to live. Domestic varieties, when turned wild, must return to something near the type of the original wild stock, or become altogether extinct.3

We see, then, that no inferences as to varieties in a state of nature can be deduced from the observation of those occurring among domestic animals. The two are so much opposed to each other in every circumstance of their existence, that what applies to the one is almost sure not to apply to the other. Domestic animals are abnormal, irregular, artificial; they are subject to varieties which never occur and never can occur in a state of nature: their very existence depends altogether on human care; so far are many of them removed from that just proportion of faculties, that true balance of organization, by means of which alone an animal left to its own resources can preserve its existence and continue its race.

The hypothesis of Lamarck--that progressive changes in species have been produced by the attempts of animals to increase the development of their own organs, and thus modify their structure and habits--has been repeatedly and easily refuted by all writers on the subject of varieties and species, and it seems to have been considered that when this was done the whole question has been finally settled; but the view here developed renders such an hypothesis quite unnecessary, by showing that similar results must be produced by the action of principles constantly at work in nature. The powerful retractile talons of the falcon- and the cat-tribes have not been produced or increased by the volition of those animals; but among the different varieties which occurred in the earlier and less highly organized forms of these groups, those always survived longest which had the greatest facilities for seizing their prey. Neither did the giraffe acquire its long neck by desiring to reach the foliage of the more lofty shrubs, and constantly stretching its neck for the purpose, but because any varieties which occurred among its antitypes with a longer neck than usual at once secured a fresh range of pasture over the same ground as their shorter-necked companions, and on the first scarcity of food were thereby enabled to outlive them. Even the peculiar colours of many animals, especially insects, so closely resembling the soil or the leaves or the trunks on which they habitually reside, are explained on the same principle; for though in the course of ages varieties of many tints may have occurred, yet those races having colours best adapted to concealment from their enemies would inevitably survive the longest. We have also here an acting cause to account for that balance so often observed in nature,--a deficiency in one set of organs always being compensated by an increased development of some others--powerful wings accompanying weak feet, or great velocity making up for the absence of defensive weapons; for it has been shown that all varieties in which an unbalanced deficiency occurred could not long continue their existence. The action of this principle is exactly like that of the centrifugal governor of the steam engine, which checks and corrects any irregularities almost before they become evident; and in like manner no unbalanced deficiency in the animal kingdom can ever reach any conspicuous magnitude, because it would make itself felt at the very first step, by rendering existence difficult and extinction almost sure soon to follow. An origin such as is here advocated will also agree with the peculiar character of the modifications of form and structure which obtain in organized beings--the many lines of divergence from a central type, the increasing efficiency and power of a particular organ through a succession of allied species, and the remarkable persistence of unimportant parts such as colour, texture of plumage and hair, form of horns or crests, through a series of species differing considerably in more essential characters. It also furnishes us with a reason for that "more specialized structure" which Professor Owen states to be a characteristic of recent compared with extinct forms, and which would evidently be the result of the progressive modification of any organ applied to a special purpose in the animal economy.

We believe we have now shown that there is a tendency in

nature to the continued progression of certain classes of varieties

further and further from the original type--a progression to which there appears

no reason to assign any definite limits--and that the same principle which

produces this result in a state of nature will also explain why domestic

varieties have a tendency to revert to the original type. This progression, by

minute steps, in various directions, but always checked and balanced by the

necessary conditions, subject to which alone existence can be preserved, may, it

is believed, be followed out so as to agree with all the phenomena presented by

organized beings, their extinction and succession in past ages, and all the

extraordinary modifications of form, instinct, and habits which they exhibit.

* * * * *

Editor's Notes

1On 18 June 1858, after receiving Wallace's essay, Darwin wrote

a letter to his colleague Charles Lyell which contained the following comment:

"Please return me the MS., which he [Wallace] does not say he wishes me to

publish, but I shall, of course, at once write and offer to send to any journal"

(Charles Darwin; His Life Told in an Autobiographical Chapter and in a

Selected Series of his Published Letters, Ed. by Francis Darwin, 1893, on

page 196). For his own part, Wallace later indicated in print on no fewer than

four separate occasions that the manuscript he had sent to Darwin had not been

intended as finished product: in an 1869 letter to the German biologist Adolf

Bernhard Meyer (later reprinted in 1895 in Nature, Volume 52, on page

415), as a note added to the essay when it was reprinted in 1891 in Wallace's Natural

Selection and Tropical Nature (on page 27), in the article 'The Dawn of a

Great Discovery' in January 1903 (Black and White, Volume 25, on page

78), and in his autobiography My Life in 1905 (Volume 1, on page 363).

2When the essay was reprinted in the collection Contributions

to the Theory of Natural Selection in 1870, Wallace added the following note

at this point: "This is under estimated. The number would really amount to

more than two thousand millions!"

3In the Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection

version the following note was added at this point: "That is, they will

vary, and the variations which tend to adapt them to the wild state, and

therefore approximate them to wild animals, will be preserved. Those individuals

which do not vary sufficiently will perish."

* * * * *

Comment by Prof. Peter Bowler, Queen's University of Belfast (pers. commun. 2/00):

The classic interpretation of Wallace's 1858 paper is that it represents an independent discovery of the Darwinian mechanism of natural selection. The paper certainly contains the description of a form of natural selection, apparently close enough to persuade Darwin himself that he had been anticipated. Yet a number of historians have argued that a close reading of the paper suggests major differences between the ways in which Darwin and Wallace formulated the idea. I have written on this subject (Bowler 1976) as to the meaning of the terms "variation" and "variety" in the paper. Darwin's theory of natural selection depends on the struggle for existence between individual variants within the same population. But the term "variety" was often used to denote what we now call subspecies--local populations differing in some well-marked way from the rest of the species. My contention is that a close reading of the paper suggests that Wallace was thinking of competition between varieties in this sense. He offers no explanation of how varieties are formed, but argues that once they are formed, they will compete with one another until only one is left, after which it will again divide into varieties to repeat the process. Significantly, Wallace saw no link between the mechanism he envisioned and artificial selection by breeders--by contrast, a key factor providing Darwin with an insight into the nature of individual selection. Note also that in versions of the paper reprinted after Wallace had read Darwin, subtitles were added which tend to enhance the impression that he was thinking of individual selection.

[Fechar]